25 maps that explain the English language

English is the language of Shakespeare and the language of Chaucer. It's spoken in dozens of countries around the world, from the United States to a tiny island named Tristan da Cunha. It reflects the influences of centuries of international exchange, including conquest and colonization, from the Vikings through the 21st century. Here are 25 maps and charts that explain how English got started and evolved into the differently accented languages spoken today.

-

Where English comes from

English, like more than 400 other languages, is part of the Indo-European language family, sharing common roots not just with German and French but with Russian, Hindi, Punjabi, and Persian. This beautiful chart by Minna Sundberg, a Finnish-Swedish comic artist, shows some of English's closest cousins, like French and German, but also its more distant relationships with languages originally spoken far from the British Isles such as Farsi and Greek. -

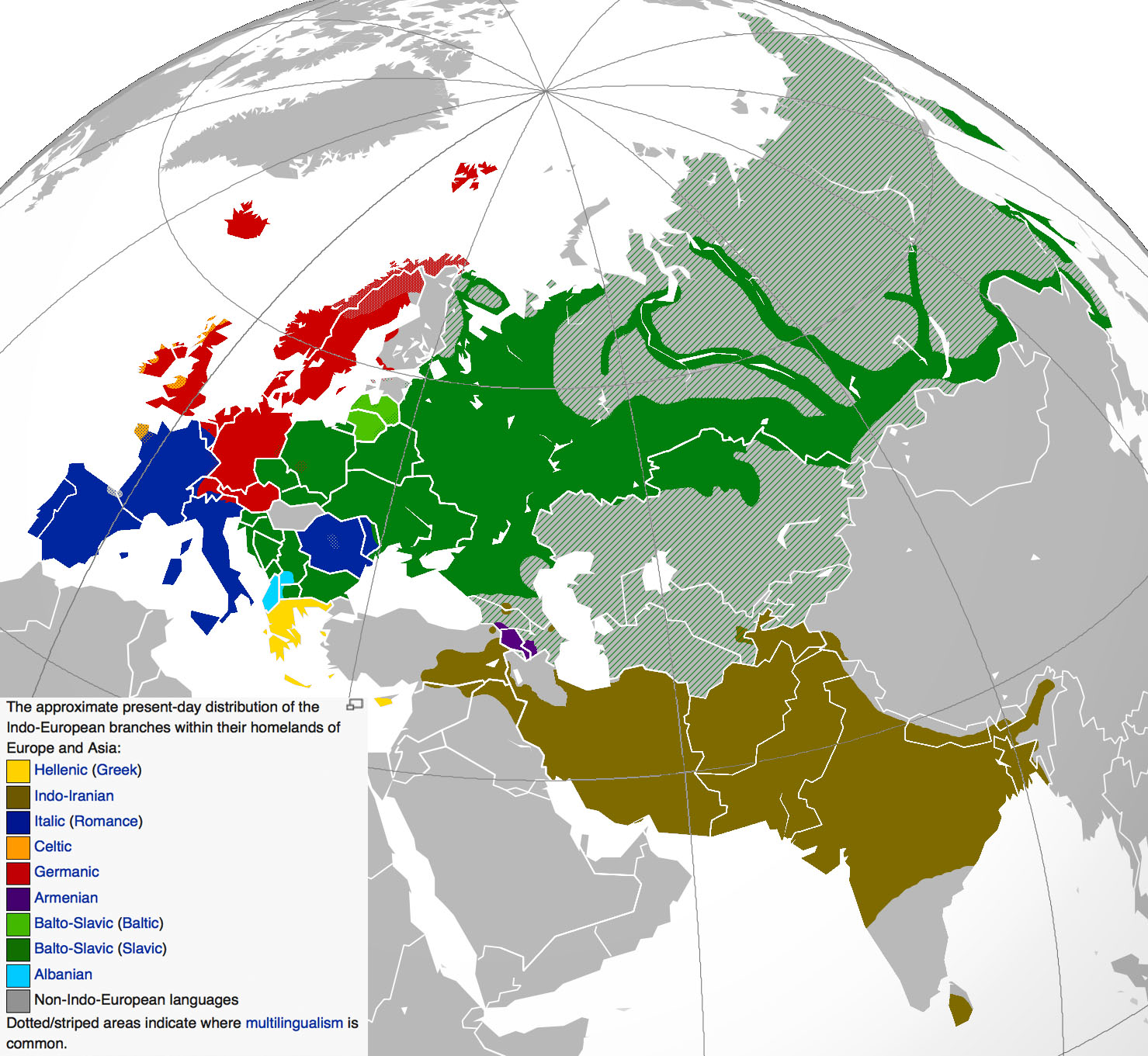

Where Indo-European languages are spoken in Europe today

Saying that English is Indo-European, though, doesn't really narrow it down much. This map shows where Indo-European languages are spoken in Europe, the Middle East, and South Asia today, and makes it easier to see what languages don't share a common root with English: Finnish and Hungarian among them. -

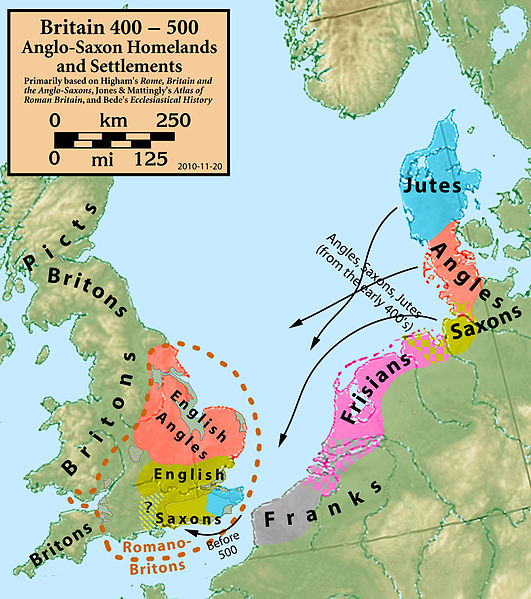

The Anglo-Saxon migration

Here's how the English language got started: After Roman troops withdrew from Britain in the early 5th century, three Germanic peoples — the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes — moved in and established kingdoms. They brought with them the Anglo-Saxon language, which combined with some Celtic and Latin words to create Old English. Old English was first spoken in the 5th century, and it looks incomprehensible to today's English-speakers. To give you an idea of just how different it was, the language the Angles brought with them had three genders (masculine, feminine, and neutral). Still, though the gender of nouns has fallen away in English, 4,500 Anglo-Saxon words survive today. They make up only about 1 percent of the comprehensive Oxford English Dictionary, but nearly all of the most commonly used words that are the backbone of English. They include nouns like "day" and "year," body parts such as "chest," arm," and "heart," and some of the most basic verbs: "eat," "kiss," "love," "think," "become." FDR's sentence "The only thing we have to fear is fear itself" uses only words of Anglo-Saxon origin. -

The Danelaw

The next source of English was Old Norse. Vikings from present-day Denmark, some led by the wonderfully named Ivar the Boneless, raided the eastern coastline of the British Isles in the 9th century. They eventually gained control of about half of the island. Their language was probably understandable by speakers of English. But Old Norse words were absorbed into English: legal terms such as "law" and "murder" and the pronouns "they," "them," and "their" are of Norse origin. "Arm" is Anglo-Saxon, but "leg" is Old Norse; "wife" is Anglo-Saxon," but "husband" is Old Norse. -

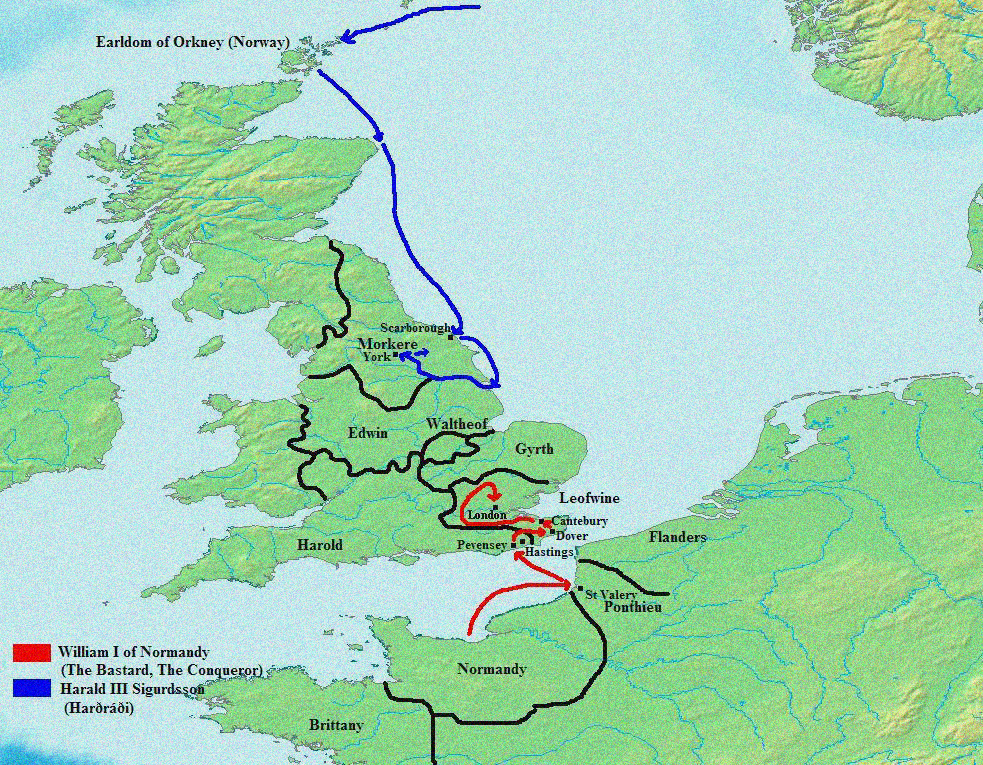

The Norman Conquest

The real transformation of English — which started the process of turning it into the language we speak today — came with the arrival of William the Conqueror from Normandy, in today's France. The French that William and his nobles spoke eventually developed into a separate dialect, Anglo-Norman. Anglo-Norman became the language of the medieval elite. It contributed around 10,000 words, many still used today. In some cases, Norman words ousted the Old English words. But in others, they lived side by side as synonyms. Norman words can often sound more refined: "sweat" is Anglo-Saxon, but "perspire" is Norman. Military terms (battle, navy, march, enemy), governmental terms (parliament, noble), legal terms (judge, justice, plaintiff, jury), and church terms (miracle, sermon, virgin, saint) were almost all Norman in origin. The combination of Anglo-Norman and Old English led to Middle English, the language of Chaucer. -

The Great Vowel Shift

If you think English spelling is confusing — why "head" sounds nothing like "heat," or why "steak" doesn't rhyme with "streak," and "some" doesn't rhyme with "home" — you can blame the Great Vowel Shift. Between roughly 1400 and 1700, the pronunciation of long vowels changed. "Mice" stopped being pronounced "meese." "House" stopped being prounounced like "hoose." Some words, particularly words with "ea," kept their old pronounciation. (And Northern English dialects were less affected, one reason they still have a distinctive accent.) This shift is how Middle English became modern English. No one is sure why this dramatic shift occurred. But it's a lot less dramatic when you consider it took 300 years. Shakespeare was as distant from Chaucer as we are from Thomas Jefferson. -

The colonization of America

The British settlers coming to different parts of America in the 17th and 18th centuries were from different regional, class, and religious backgrounds, and brought with them distinctive ways of speaking. Puritans from East Anglia contributed to the classic Boston accent; Royalists migrating to the South brought a drawl; and Scots-Irish moved to the Appalaichans. Today's American English is actually closer to 18th-century British English in pronunciation than current-day British English is. Sometime in the 19th century, British pronunciation changed significantly, particularly whether "r"s are pronounced after vowels. -

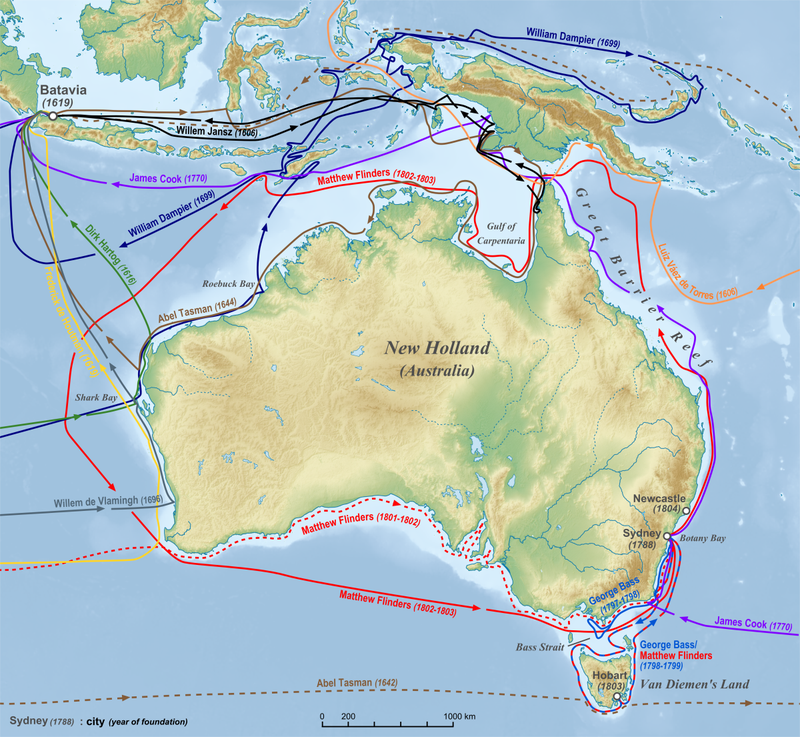

Early exploration of Australia

Many of the first Europeans to settle in Australia, beginning in the late 1700s, were convicts from the British Isles, and the Australian English accent probably started with their children in and around Sydney. Australia, unlike the US, doesn't have a lot of regional accents. But it does have many vocabulary words borrowed from Aboriginal languages: kangaroo, boomerang, and wombat among them. -

Canada

British Loyalists flooded into Canada during the American Revolution. As a result, Canadian English sounds a lot like American English, but it's maintained many of the "ou" words from its British parent (honour, colour, valour). There's also some uniquely Canadian vocabulary, many of which is shown in this word cloud. Canada is undergoing a vowel shift of its own, where "milk" is pronounced like "melk" by some speakers. But unlike British and American English, which has a variety of regional accents, Canadian English is fairly homogenous. -

English in India

The British East India Company brought English to the Indian subcontinent in the 17th century, and the period of British colonialism established English as the governing language. It still is, in part due to India's incredible linguistic diversity. But languages from the subcontinent contributed to English, too. The words "shampoo," "pajamas," "bungalow," "bangle," and "cash" all come from Indian languages. The phrase "I don't give a damn" was once speculated to refer to an Indian coin. This probably isn't true — the Oxford English Dictionary disagrees — but it shows that language exchange during the colonial era was a two-way street. -

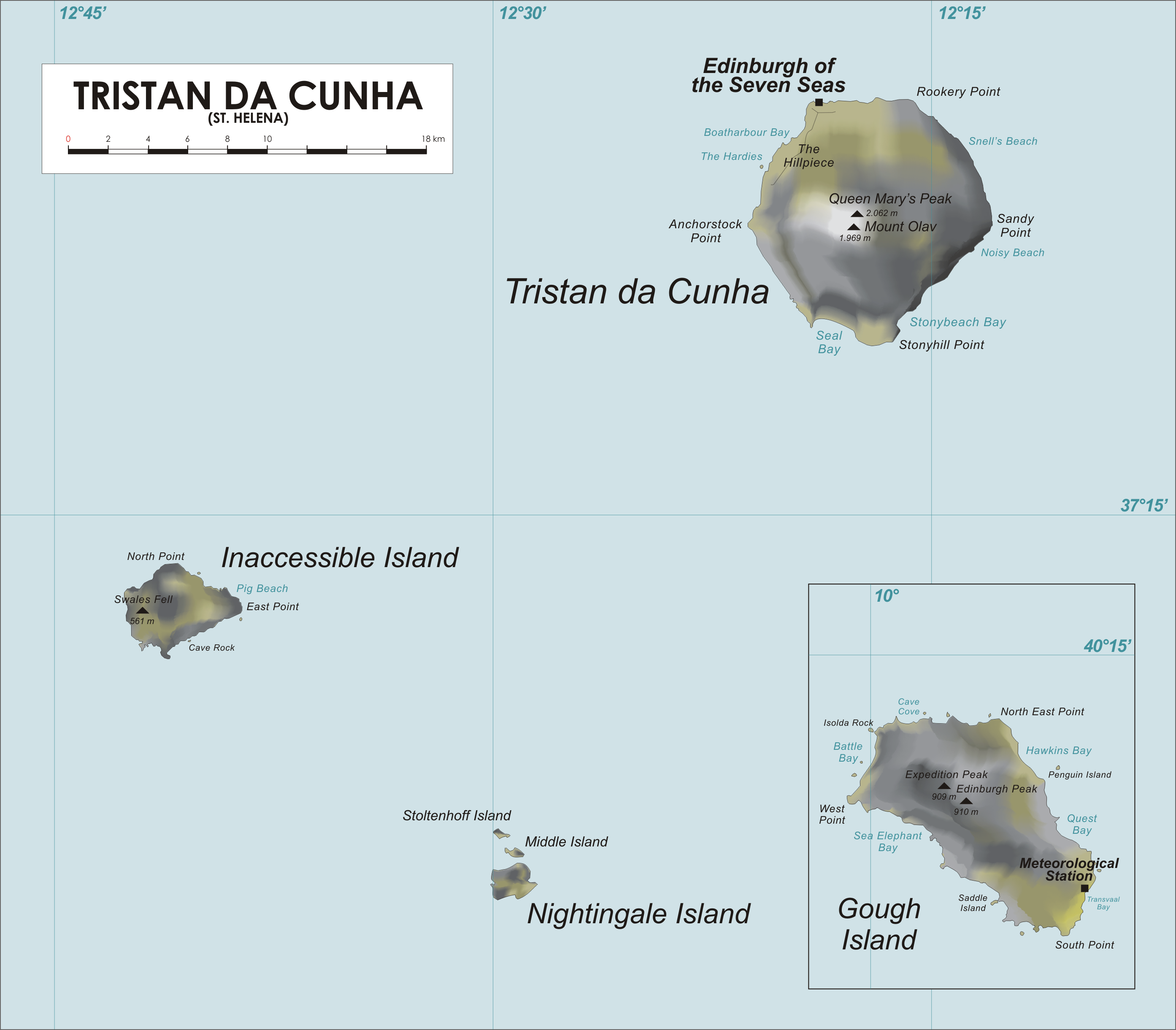

Tristan da Cunha

Tristan da Cunha is the most remote archipelago in the world: it's in the South Atlantic Ocean, more or less halfway between Uruguay and South Africa. It's also the furthest-flung locaction of native English speakers. Tristan da Cunha is part of a British overseas territory, and its nearly 300 residents speak only English. Tristan da Cunha English has a few unusual features: double negatives are common, as is the use of "done" in the past tense ("He done walked up the road.") -

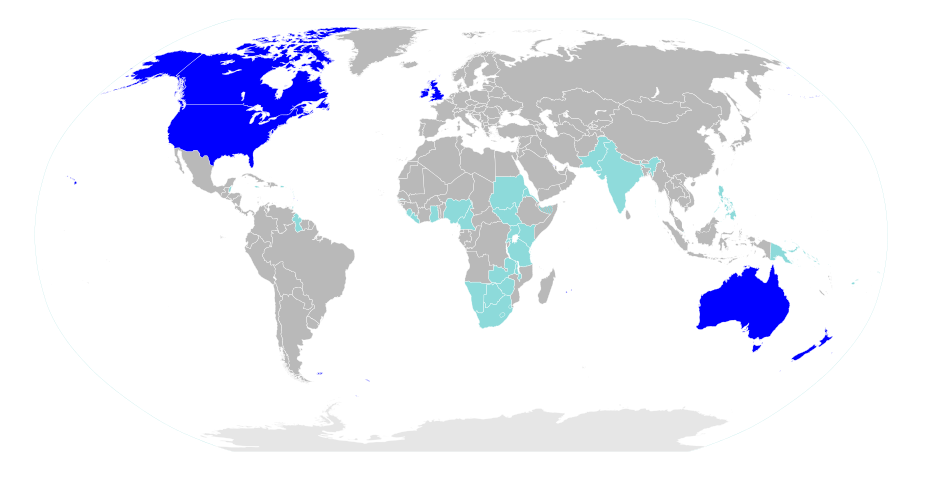

Countries with English as the official language

Fifty-eight countries have English as an official language. This doesn't include most of the biggest English-speaking countries — the United States, Australia, and the United Kingdom don't have official languages. This map shows where English is either the official or the dominant language. Particularly in Africa, it also doubles as a fairly accurate map of British colonial history. -

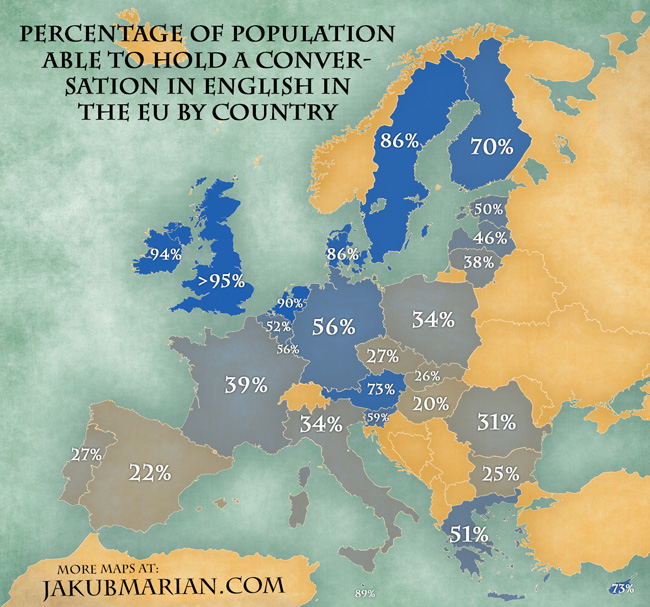

Which countries in Europe can speak English

English is one of the three official "procedural languages" of the European Union. The president of German recently suggested making it the only official language. But how well people in each European Union country speak English varies considerably. This map shows where most people can — and can't — have an English conversation. -

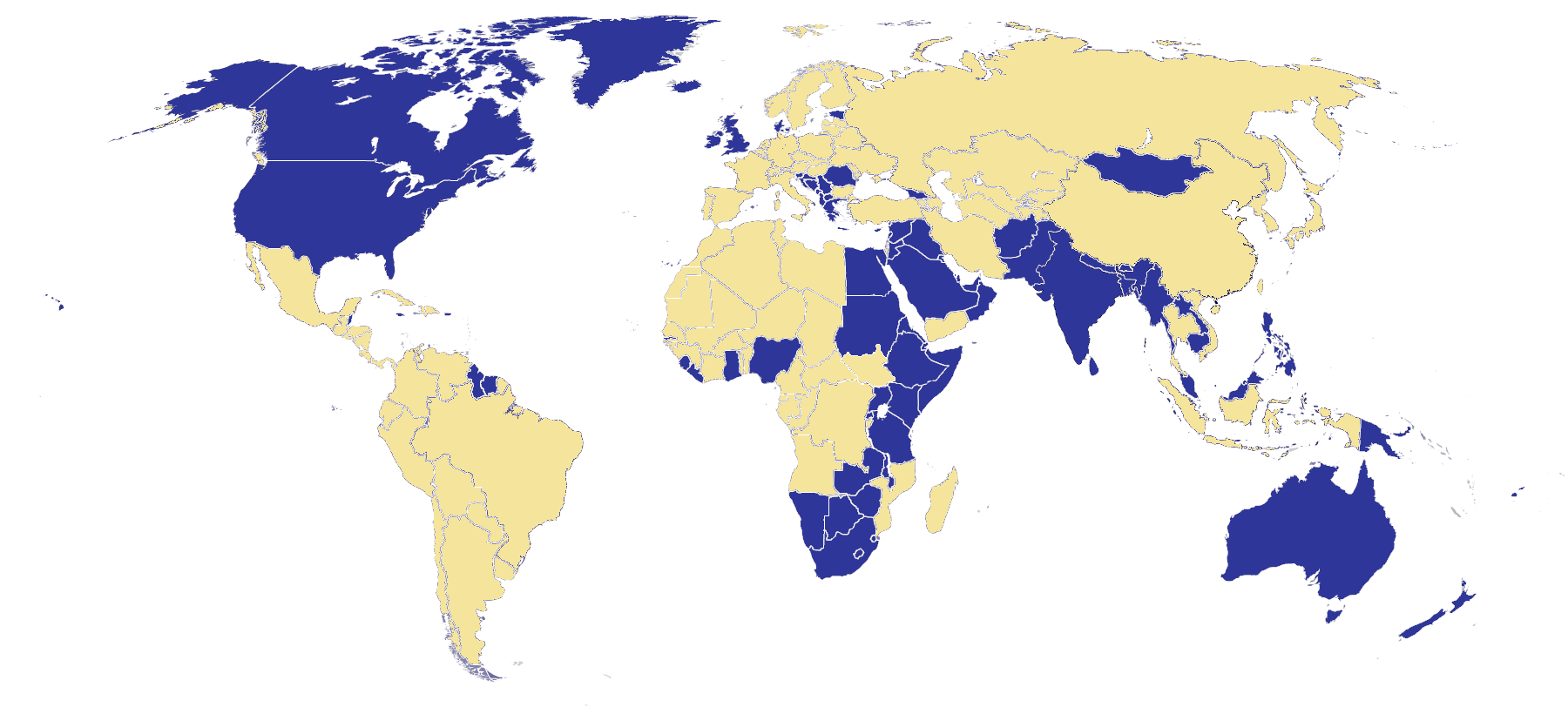

Where people read English Wikipedia

English dominated in the early days of the Internet. But languages online are getting more diverse. In 2010, English no longer made up the majority of the text written online, as advancements in technology made it easier for non-Roman alphabets to be displayed. Still, English is the dominant language of Wikipedia — both when you consider the language articles are written in, and where people use the English-language version, as is shown in this map. -

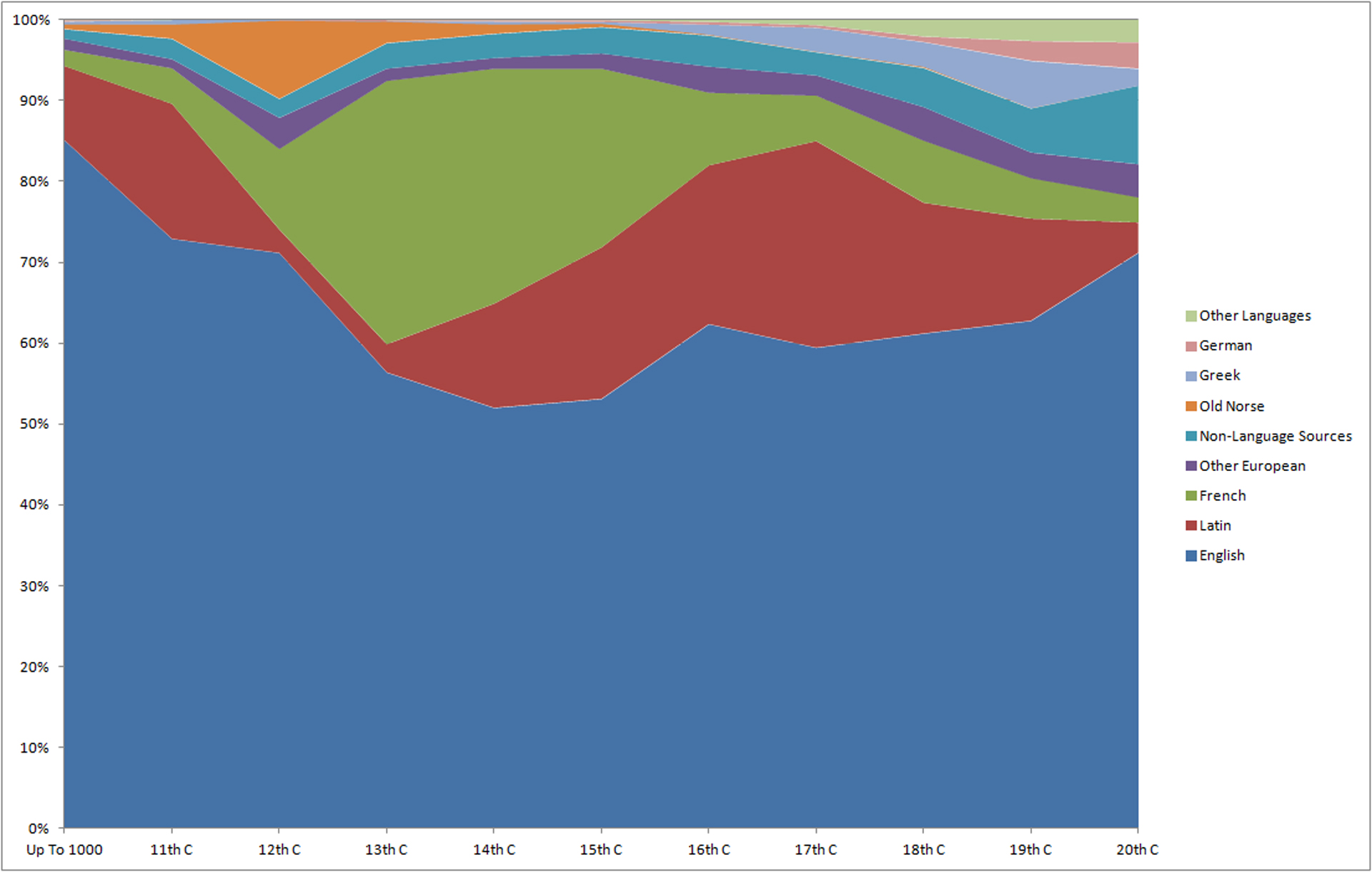

Where new English words come from

This fascinating chart based on data from the Oxford English Dictionary shows where words originally came from when they first started to appear in English. Most words come originally from Germanic languages, Romance languages, or Latin, or are formed from English words already in use. But as this screenshot from 1950 shows, words also come to English from all over the world. -

How vocabulary changes based on what you're writing

Borrowing words from other language didn't stop when Old English evolved into Middle English. The Enlightenment brought an influx of Greek and Latin words into English — words for scientific concepts that moved into broader use as science developed. Scientific vocabulary is still usually based on Greek or Latin roots that aren't used in ordinary conversation. On the other hand, Mark Twain, master of the American dialect, relied heavily on good old Anglo-Saxon words in his work, a reflection of the endurance of those very old words for the most ordinary concepts in everyday life. -

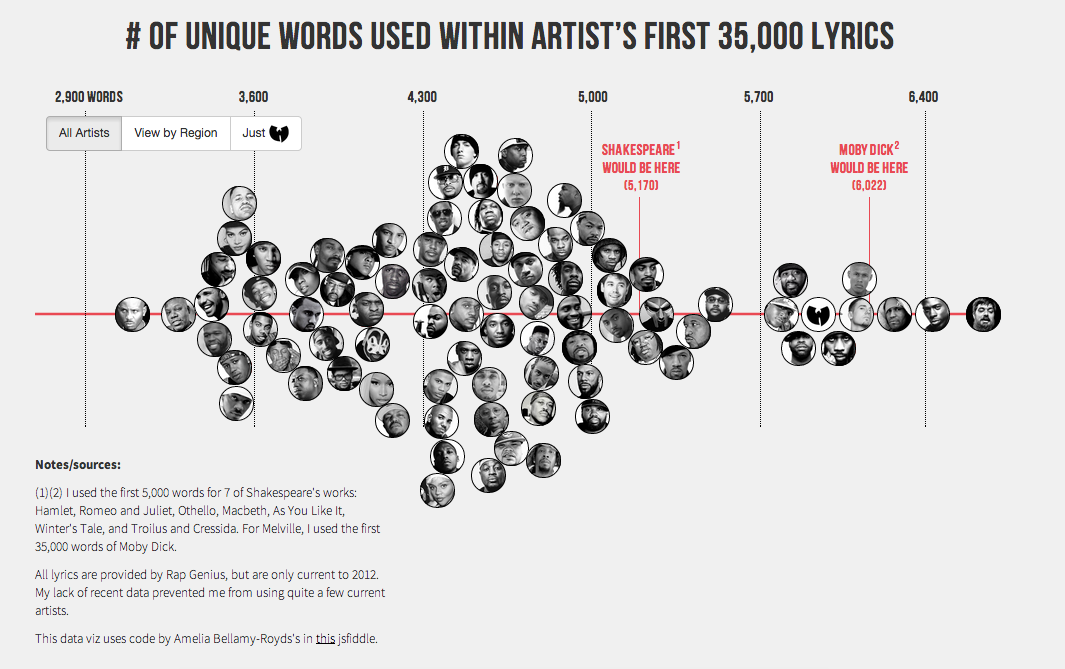

Vocabulary of Shakespeare vs. rappers

Designer Matt Daniels looked at the first 35,000 words of artists' rap lyrics — and the first 35,000 words of Moby-Dick, along with 35,000 words from Shakespeare's plays — to compare the size of their vocabularies. He found that some have bigger vocabularies than Shakespeare or Melville. Of course, vocabulary size isn't the only measure of artistry. But it's an interesting look at how English has changed. -

Where English learners speak the language proficiently

English is the second most-spoken language in the world. But there are even more people learning English (secondary speakers) than people who claim English as their first language. Here's where people tend to score well and poorly on tests of English from Education First. Green and blue countries have higher proficiency levels than red, yellow and orange ones. Scandinavian countries, Finland, Poland, and Austria fare best. The Middle East generally lacks proficient English speakers. -

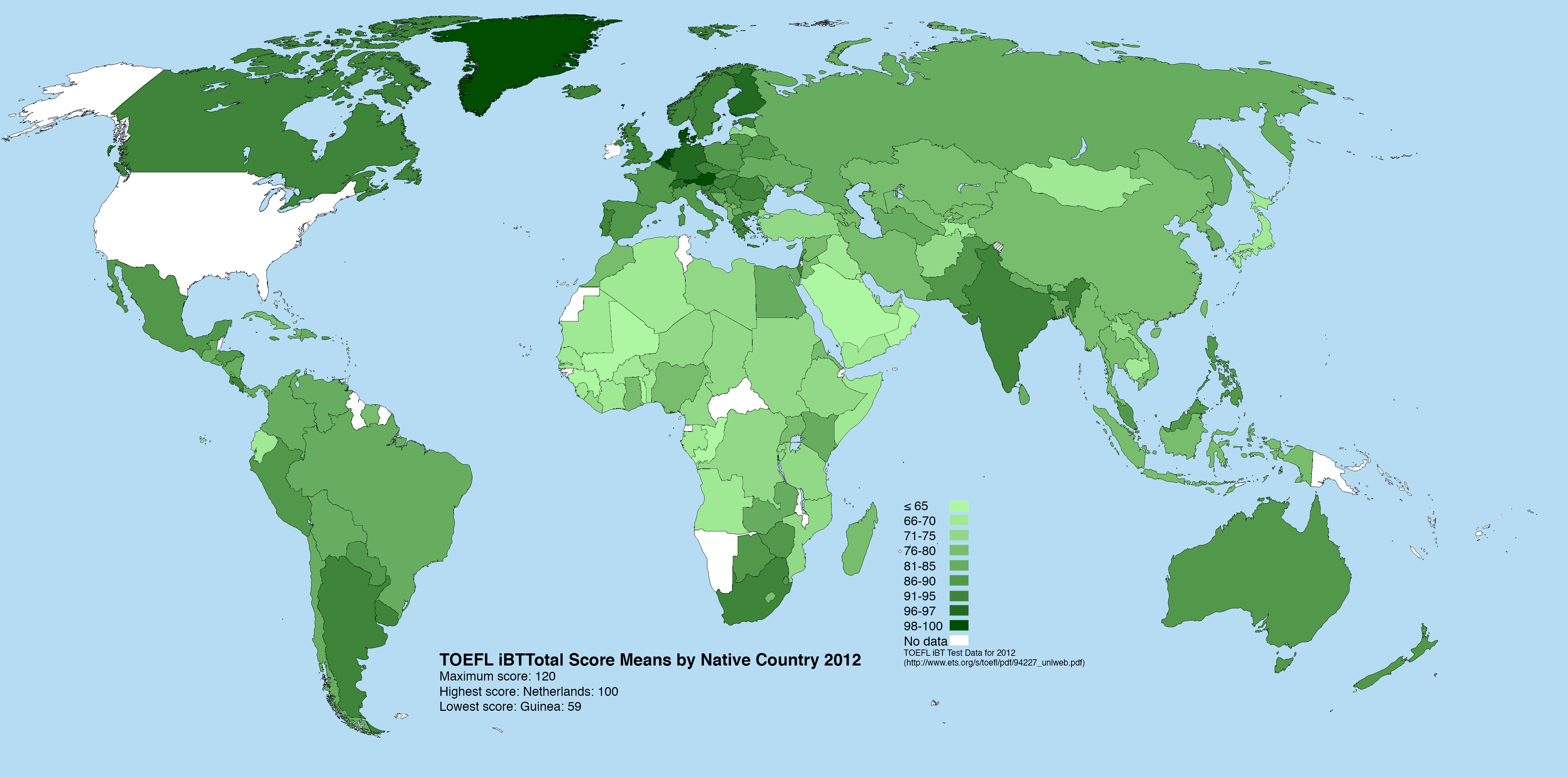

Scores on the Test of English as a Foreign Language

The Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) is required for foreign students from non-English-speaking countries to enroll at American universities, among other things. Here's where students tend to perform well. (English-speaking countries are included on the map, but the test is only required for people for whom English is not a first language.) The Netherlands gets the top score: an average of 100 points out of a possible 120. -

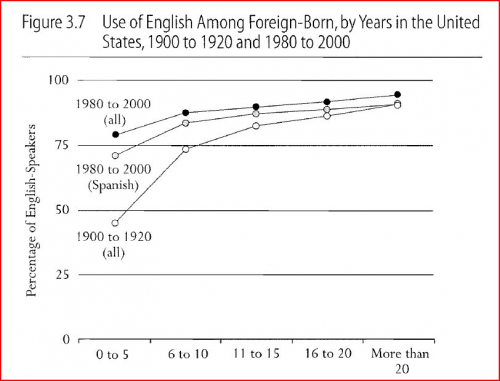

Immigrants to the US are learning English more quickly than previous generations

Concerns about whether immigrants are assimiliating in the US often focus on criticisms that they're not learning English quickly enough (think of outrage over phone systems that ask you to select English or Spanish). But in fact immigrants to the US today are learning and using English much more quickly than immigrants at the turn of the 20th century. More than 75 percent of all immigrants, and just less than 75 percent of Spanish-speaking immigrants, speak English within the first five years, compared to less than 50 percent of immigrants between 1900 and 1920. -

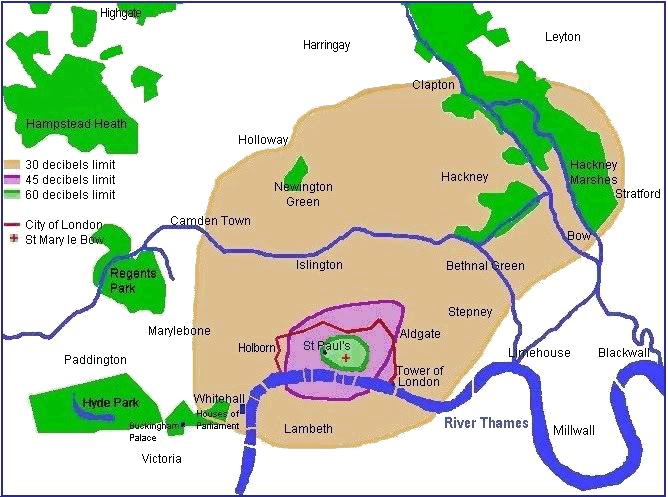

Where Cockneys come from

The traditional definition of a Cockney in London is someone born within earshot of the bells of St.-Mary-le-Bow church -- the area highlighted in tan on this map. (The smaller circles within it are where the bells can be heard more loudly in the noisier modern world.) The distinctive Cockney accent or dialect is best known for its rhyming slang, which dates back to at least the 19th century. The slang starts as rhymes, but often the rhyming word is dropped — "to have a butcher's," meaning "to take a look," came from the rhyming of "butcher's hook" with "look." The phrase "blow a raspberry" — which has spread far beyond London — originally comes from the rhyming of "raspberry tart" with "fart.") -

Dialects and accents in Britain

There are three general types of British accents in England: Northern English, Southern English, and the Midlands accent. One of the most obvious features is whether "bath" is pronounced like the a in "cat" (as it is in the US and in Northern English dialects) or like the a in "father" (as it is in Southern English dialects). The generic British accent, meanwhile, is known as "Received Pronunciation," which is basically a Southern English accent used among the elite that erases regional differences. Here's a video of one woman doing 17 British accents, most of which are shown on the map. -

North American vowel shift

There's another vowel shift going on in American English right now. In the Great Lakes region, short vowel sounds are changing. This is remarkable because short vowel sounds (think of the short "a" in "cat," rather than the long a in "Kate") actually survived the Great Vowel Shift in the 17th century. Short vowel sounds haven't changed for hundreds of years — but now they are, in Milwaukee, Chicago, Cleveland, and other cities and even small towns around the Great Lakes, at least among white speakers. "Buses" is pronounced like "bosses." "Block" comes out like "black." Nobody's sure why, but it appears to have started as long ago as the 1930s. The map shows which areas have adopted various stages of the vowel shift. -

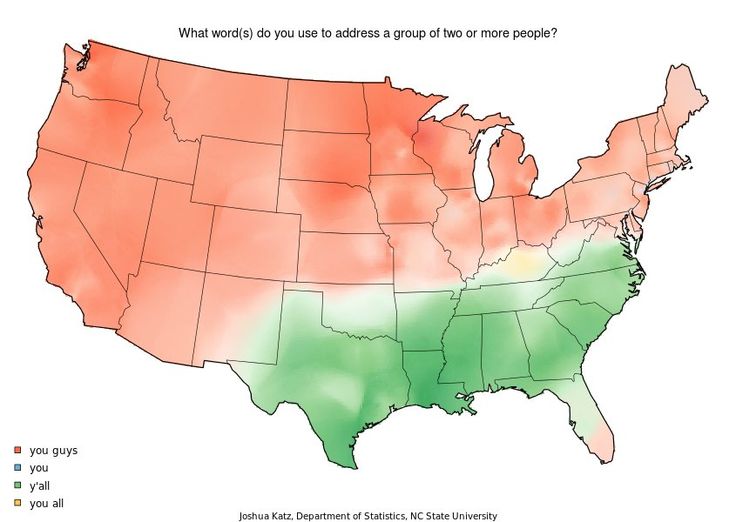

American dialects

Here's a detailed map of how Americans talk. The bright green dialects are all subsets of "general Northern" — a generic American accent used by about two-thirds of the US, according to linguist Robert Delaney, who built this map. But it includes many subsets. The Eastern New England accent is the "pahk the cah in Hahvahd Yahd" accent. In the South, you can see how English has and hasn't changed over generations. The South Midland accent retains some words from Elizabethan English. And the Coastal Southern accent retains some colonial vocabulary, like "catty-corner."

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario

Find your motivation. Find your inspiration. All you have to do is start reading, absorbing, and implementing.